Beachcombing and Grave Goods: Connectivity through Objects

December 2, 2015 by Jess

written by Sarah Fagan,

2015-2016 Artist-in-Residence

Earlier this month I gave my first talk as the Umbrella's Artist-in-Residence. The topic was the meaningful use of emptiness in art: the power of a Rothko color field, for example. After much musing about the utility of emptiness this month, the world was sure to remind me of the yin to the yang of the void. So this post is not about emptiness. It is about things.

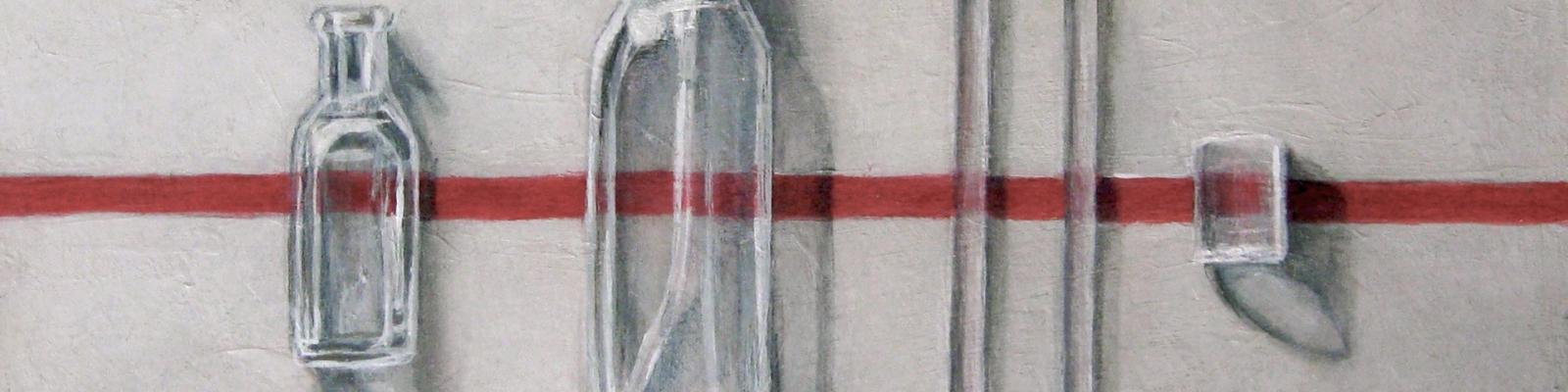

A recent trip to a long stretch of beach in Newburyport, MA was a vision of nature at its best. I marveled at perfect moon snail shells, whole sand dollars, and the shapes of tide lines. Yet I recall my heart truly skipping a beat at a glimpse of something sparkling green: half of a glass bottle, worn smooth in the saltwater, sticking out of the sand. Why did this manmade object bring me joy? It was a totem of humankind. A reminder that others had been there before. In that moment, the lone bottle registered not as litter (a problem, to be sure), but a glimmer of connectedness and familiarity.

Back in Concord, the more famous grave sites in Sleepy Hollow Cemetery boast a phenomena common amongst headstones belonging to beloved public figures. Out of reverence, pilgrimage, or simply a desire to join in on the fun, some visitors leave small goods at the graves. These tokens are a mix of purposefully brought and fished-from-the-pocket artifacts. Coins, beads, seashells, pencils, notes, and sometimes whole books are left at the graves of Emerson, Alcott, Hawthorne, and, most often, Thoreau -- all but engulfing the simple stone bearing the sole word "Henry." Every so often the goods are cleared away and the process begins anew, not unlike objects washed in and out with the tide.

I can't help but think that folks who leave these items, these little parts of them, feel the same thrill that I felt when finding the glass bottle on the beach. The ritual provides a connection to other humans that have left objects before, and those who will discover the objects later. It even provides a connection to the life of one that came long before -- commemorated no longer by just a stone, but by pennies and pencils, too. Perhaps this feeling of connectedness is what draws me to collect, save, and render objects in my paintings. Tangible things remind us that we are here, and are not alone.